As part of 2014’s Glasgow Film Festival, Documenting Grierson, a film by Laurence Henson, was screened, allowing the audience an all too brief encounter with the ‘father of documentary’ John Grierson. Henson’s film highlights the importance and influence of Grierson’s philosophies and ideologies regarding cinema, social welfare and education during the interwar years in Britain.

In an excerpt from Henson’s film, Grierson talks passionately about the purpose of documentary as being, “A chance to say something, a chance to teach something, a chance to reveal something, a chance, possibly to inspire, certainly always an opportunity for influence of one kind or another.” Grierson wrote a lengthy manifesto outlining the principles of documentary, discussing the ethical issues and function of filmmaking (ref. Grierson Archive, G2.15.2). Today the artistic and pedagogical significance of documentary filmmaking continues, with The Grierson Trust awarding accolades each year to the most inspiring films. Academically, documentary techniques are rigorously theorised, crucially analysing the distinction between the ‘real’ or non-fiction aspect and the fictitious or ‘wish-fulfillment’ style, as pioneering documentary theorist Bill Nichols suggests.

Early on in his career John Grierson decided that producing films would be more advantageous to the cause, especially when negotiating for government funding. He employed like-minded people to execute technical duties such as, camera work and editing. The core production crew consisted of, Harry Watt, Edgar Anstey, Basil Wright and Stuart Legg, a mix of aspiring young filmmakers. Grierson’s tenacity and ability to get things done changed the way we viewed the world and through the Empire Marketing Board film unit, headed by chief commissioner Stephen Tallents, society was presented with information, education and choice – a testament to the power of cinema (ref. Grierson Archive, G4.31.3).

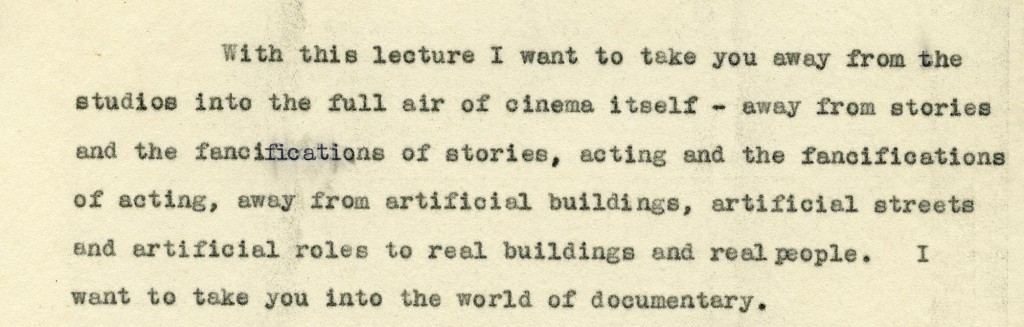

Grierson encouraged others with his documentary making views through lectures and publications, sometimes subversively, but always expressing an over-arching importance. He is quoted in The Daily Herald (1935) saying, “I wish the B.B.C., instead of sterilizing its speeches in the cabins of Broadcasting House, would take its microphones out to the people” (ref. Grierson Archive, G3.14.1). A method that Arthur Elton and Edgar Anstey incorporated in their film Housing Problems (1935) – an idea attributed to John’s sister Ruby Grierson, also a filmmaker.

Grierson dealt his contemporaries with equal amounts of contempt and praise. In an article in Cinema Quarterly (1932), he pitted other disciplines against the prestige of documentary – “newsreel is just a speedy snip-snap of some utterly unimportant ceremony”, continuing to say, “[they] avoid…the consideration of any solid material” (ref. Grierson Archive, G2.15.2). However acerbic Grierson’s humor might have sounded, the importance of documentary and for those involved was paramount.

The British Documentary Movement went into decline after the Second World War and as a consequence of those who had experienced ‘real’ war, the documentary style became more about technique than content. As the political restructuring of Britain began, Grierson’s production unit splintered and with the introduction of television to the mass audience in 1953, produced a new style of documentary. Grierson et al welcomed this shift and went on to produce a variety of documentaries for the new medium.

(Susannah Ramsay, M. Litt. in Film Studies)