A SGSAH internship, a Collaborative Outreach Project, and a Collection of Skulls, Skeletons, and Shells

In this blog post Art Collection intern, Maddie Reynolds, shares her experience of working with the science collections at the University of Stirling.

When the 2023 SGSAH (Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities) internship positions were first advertised, I was eager to explore the possibility of stepping outside my PhD project and integrating practical-work experience into my academic life. The process of writing a PhD is rewarding, but exhausting, and while it is exciting to be the steward of your own original research, the constant cycle of research, write, edit, write, and repeat can be monotonous. PhD projects are also incredibly niche, and though I am fortunate to work within a network of other supportive, enthusiastic, and engaged early modernists and ‘material culturists’, the chance to step outside of that space and revisit my larger interests – object handling, display, collection care, and public engagement – in new setting was an opportunity too good to ignore.

The University of Stirling Art Collection team advertised a position that would allow the successful applicant to work with a collection of scientific objects that had recently come under their remit. My own PhD project combines History of Science, History of Art, and material culture methodology to investigate alchemical or alchemically themed objects as tools of self-fashioning in sixteenth and seventeenth century England. While Stirling’s collection of objects is from the twentieth century, the combination of science, art, and object handling felt applicable in a way that was at once removed from my research and still relevant to it.

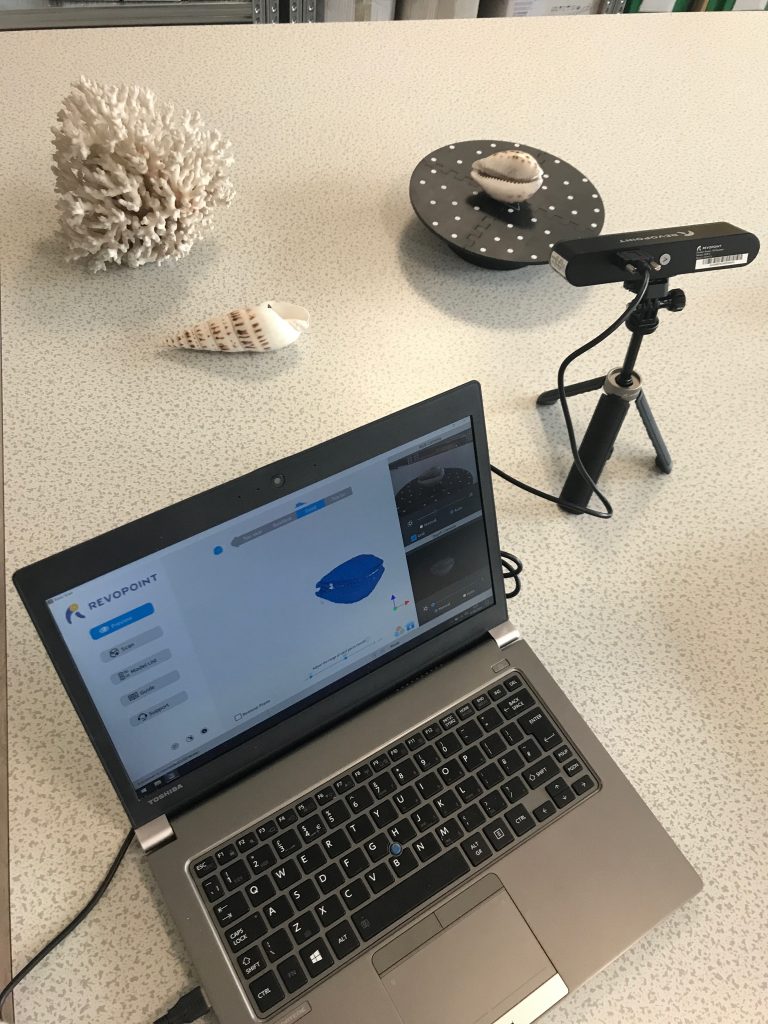

This project included the chance to investigate the scope of a collection of objects that was under-researched and underutilised, as well as consider the ways in which it could be catalogued, displayed, stored, and cared for in the long-term. In addition to cataloguing, the project consisted of 3D scanning, several outreach events, and the chance to work with academics from the Faculty of Natural Sciences. These added features became invaluable to my learning experience – as an academic who works with objects and their functional, every day applications as a conceptual starting point for research, the ins-and-outs of 3D scanning is relevant to the practical obstacles I sometimes face as I consider ideas of haptic engagement and the meanings created when people and objects interact. Understanding, first-hand, the technological process of 3D scanning and the way it can elevate a catalogue entry, or allow for a more comprehensive learning experience, was something I had not considered up until this point. I find technology to be intimidating and occasionally frustrating, so this specific part of the internship would push me out of my comfort zone.

The outreach events, and collaboration with academics, would also round-out my internship. I was interested to see how the Art Collection team would approach these objects; I think there is often a misconception that those who work in the arts and those that work in the sciences have no common ground. Old ideas of scientists and mathematicians being ‘left-brained’ and artists, historians, and creatives being ‘right brained’ have long separated the two subjects – science and art – both of which are rich with interdisciplinary opportunity. This arbitrary division is ignored by the Art Collection team, who aim to foster a space for integrative learning both within the academic community at the University of Stirling and the wider community it serves.

After a successful interview with Sarah Bromage, Head of Collections, and Emma McCombie, Deputy Head of Collections, I was delighted to be offered the opportunity to work with a team of people who seemed as excited to work on the project as I was. My first day was nothing but positive – the entirety of the team, beyond Sarah and Emma, as well as the other members of staff, from the Natural Sciences faculty to the Archives staff, were nothing but helpful and encouraging.

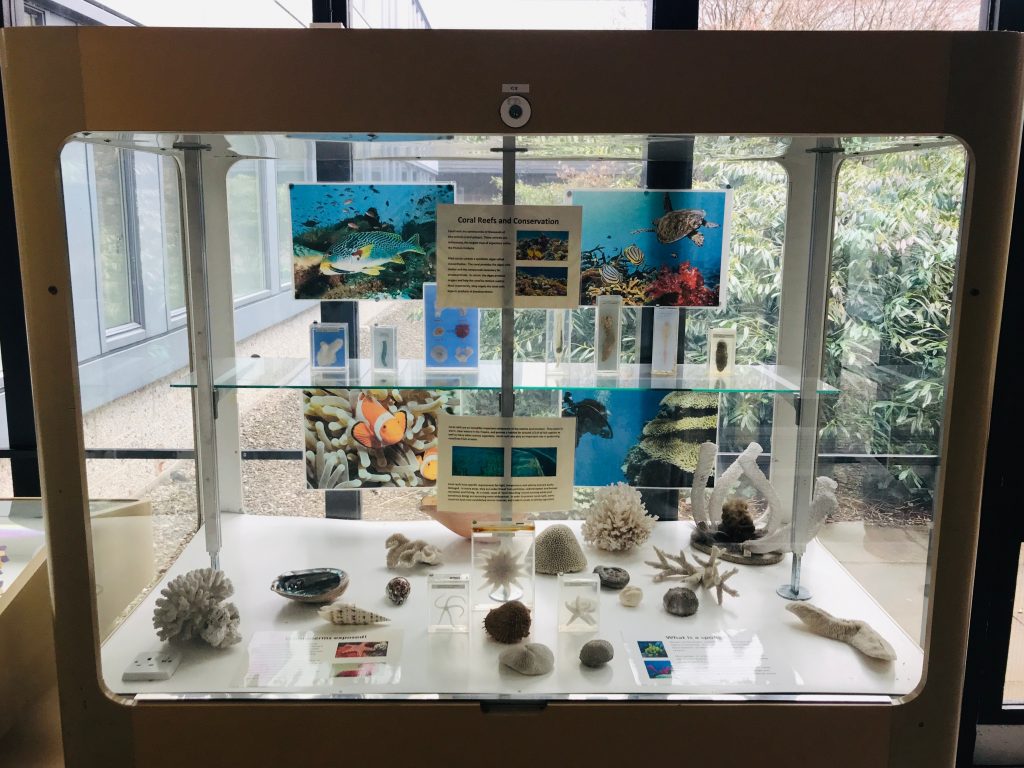

At first glance, the project appeared to be straightforward: understanding the scope of a collection and cataloguing it for future research and use. But the interdisciplinary value of this endeavour, and its essential capacity to traverse modalities, mediums, and disciplines, has resulted in a project that finds science and art at a crossroads – but not one in which these subjects diverge. By reflecting on shared methodologies, material processes, modes of observation, and similar points of creative inquiry, this project has yielded various visual and material iterations of a collection of natural science objects, giving them an afterlife that extends beyond a display cabinet.

These ‘things’ are understood for their texture and their weight, for their past life in an elaborate marine ecosystem, and as objects capable of generating artistic inspiration. Shells, skeletons, and skulls alike have been photographed and 3D scanned, generating visual teaching and research aids that will form a forthcoming catalogue. The many versions of these objects and first-hand engagement with them from a multi-disciplinary perspective was the basis of the outreach series, spearheaded by Emma McCombie and Sarah Bromage, a dynamic duo who are experts in making art approachable, enjoyable, and positively impactful.

The outreach element of project has since brought together a wide range of creative people: The Pathfinders – a group of environmentally-minded young students from different schools in the Stirling area; art students from Forth Valley College; staff and PhD students from the University of Stirling; Dr Zeinab Smilie, a lecturer in environmental and geoscience at Stirling whose niche knowledge of marine specimens provided context and understanding of even the most unfamiliar objects; and Emma Hislop, a creative and passionate Edinburgh-based artist (who laughingly cites her initial interest in flammable art processes as something that began when she accidentally set her parent’s living room on fire as a child). In addition to her humour, Emma’s serious enthusiasm for sharing her art and her expertise brought a commemorative and innovative component to the workshops as she walked the various groups through creating decorative designs in cuttlefish moulds after which she melted pewter for them to cast their own coins.

My personal aims for the project are ongoing – continuing 3D scanning, finishing the catalogue, and creating an online exhibition featuring these objects. But with two months left, I am excited to say that this internship has been fundamental to my understanding of what it means to consider interdisciplinary approaches for gaining and sharing knowledge, both academically and practically. In the (exhausting) world of grant applications and chronically underfunded art and academic spaces, buzzwords like ‘interdisciplinary’ are often stated for impact, as a means to an end – but this project and the collaboration of people across disciplines and backgrounds, the creation of a catalogue of teaching tools and research objects, and the positive impact of these outreach events, is the end in itself.