The University of Stirling’s Art Collection is home to a significant collection of original 1960s furniture that decorated the university’s buildings when it was first established in 1967. These pieces, ranging from sofas and chairs to sideboards and tables, offer a central point of insight into both the stylistic developments of the period and the aesthetic environment created within the newly founded University of Stirling.

The 1960s ushered in a new generation of designers and aesthetic ideals which saw the rejection of the solid values of 1950s organic modernism and, instead, embraced experimentation and formal innovation. This aesthetic revolution coincided with and responded to an era of unprecedented change in which going against the establishment and traditional tastes was central to the development of design. Throughout the 1950s, design was profoundly influenced by the rationing and the austerity of the post Second World War years, resulting in furniture that was strictly utilitarian, unemotional, and functional. However, as prosperity and private affluence began to grow in the late 1950s and early 1960s, consumers had more money to spend on goods and were no longer solely concerned with functionality.

This economic shift and focus on social mobility impacted tastes, as design became a social language through which to communicate one’s position in society. Designers responded accordingly, creating works that pushed the parameters of what was thought possible and innovating with new materials and technologies.

Through this, furniture and interior design of the 1960s became characterised by bold colours, new materials, and fluid and dynamic forms. Instead of following the pedagogy that “form follows function,” designers began to regard their work as part functional, part sculptural pieces that pushed the boundaries of what was possible to open formal possibilities. Long gone were the days when furniture could simply be regarded as a utilitarian item; instead, these pieces became culturally loaded symbols that expressed progress, identity, and aspirations.

By caring for this collection of the University’s original furniture, the Art Collection ensures that the legacies of these pieces and their rich histories are protected, allowing us to reconstruct an image of the past.

The Diamond Chair, designed by Italian-born sculptor Harry Bertoia, is a classic example of 1960s design. Bertoia, who often used wire and rod in his own artwork, translated this into his furniture designs. The Diamond chair, made from welded steel with rods in polished or satin chrome, was designed to be ‘mainly made of air, like sculpture. Space passes right through them,’ (Bertoia). The seat, made from a single, concave grid of wires, appears delicate and weightless in its construction, belying its strength and durability. The chair was first designed in 1952 and manufactured in 1953 and marked a landmark achievement in the design of modern furniture. The chair continues to be manufactured and sold today, transcending the ages with its timeless design. This piece was designed for Knoll, an international design company and furniture manufacturer that was established in New York in 1938 by Hans Knoll, son of Walter Knoll, a successful second-generation furniture manufacturer. Later joined by architect Florence Schust, both leaders of the company were fundamentally inspired and led by the principles of the Bauhaus School in Weimar, Germany, believing that modern furniture should complement architectural space and joining craftsmanship with technological innovation. Over 40 Knoll designs can be found in the permanent design collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, a testament to the profound impact of Knoll’s designs and the significance of furniture on the world of art and visual culture.

The ‘Ant Chair’, perhaps best recognised by those familiar with the university campus as the chairs of the MacRobert Art Centre, is another prime example of 60s design. This chair was designed by Arne Jacobsen for the Danish company Fritz Hansen. Constructed from 9 hand-cut sheets of pressure moulded veneer, the chair is cut by hand to achieve the signature shape of the chair, inspired by the outline of an ant with its head raised. Originally designed with three legs, the company later developed a second iteration of the chair with four, examples of which are held in the University of Stirling’s collection. The chair was designed to be light, stable, and easily stackable, blending functionality with the elegant and streamline aesthetic of Scandinavian design. While Fritz Hansen originally had reservations about the Jacobsen’s design, the chair quickly became a commercial success and has been in production ever since. The international popularity of this piece, especially within Britain, reflects the strong influence and taste for Scandinavian design.

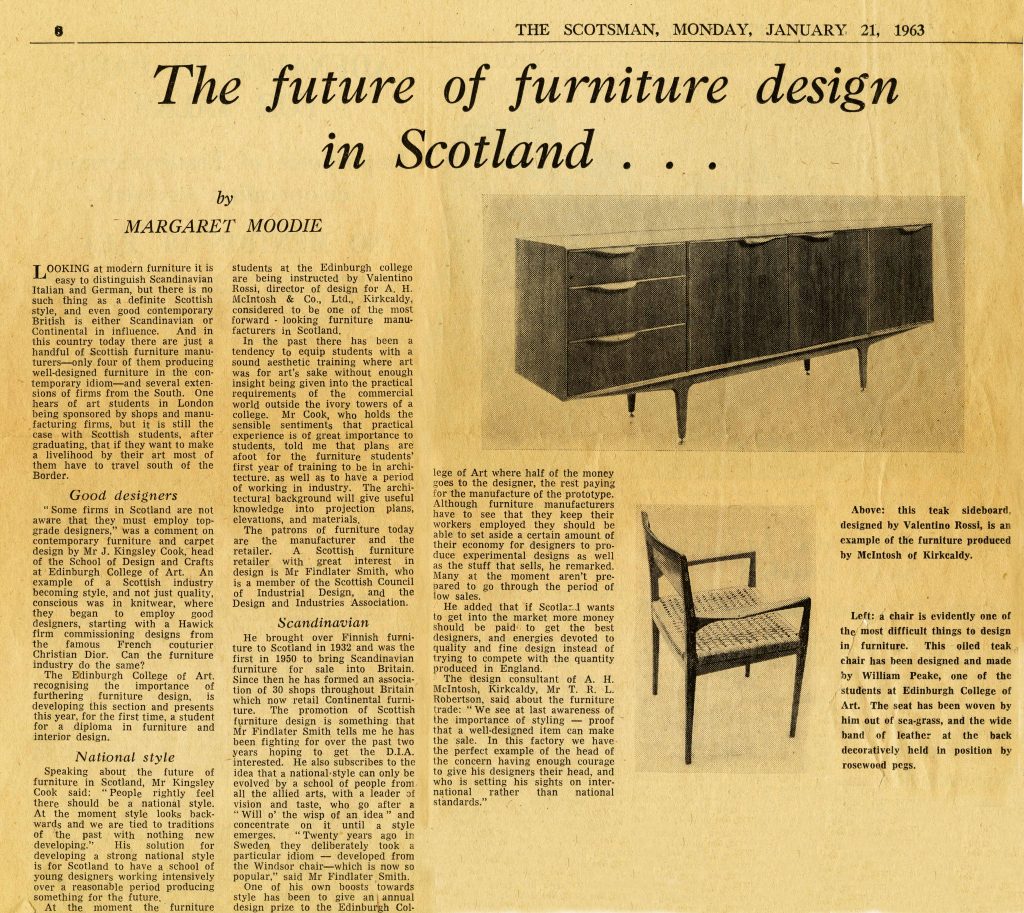

As well as turning towards experimentation, British designers were also heavily influenced by the Scandinavian style of furniture that prioritised handcraftsmanship and the use of fine woods such as teak and rosewood. The British furniture industry was in fierce competition with Scandinavian manufacturers, as imports of furniture, particularly from Sweden and Denmark, rose substantially throughout the late 50s and 60s. Thus, British furniture design in the 1960s oscillated between traditional materials with an emphasis on craftsmanship and experimentation with new materials and organic forms. Danish design became the hallmark of good taste among the middle classes, with Scandinavian sideboards being particularly in vogue. British designers responded to this by developing their own Scandinavian-inspired designs, as exemplified in the teak sideboards manufactured by A.H. McIntosh.

These sideboards were among the most successful designs by A.H. McIntosh, reflecting the high demand for Scandinavian design among British consumers. The Dunvegan Teak Sideboard, designed by Valentino Rossi under the company leadership of head designer Tom Robertson, is one of the most prominent and famous examples of design by McIntosh, with the sculpted handles lending the sideboard a more contemporary touch, while remaining connected to the traditional design that underpinned the Scandinavian aesthetic. However, despite drawing heavily on this stylistic influence, A.H. McIntosh always marketed itself as a Scottish firm that utilised traditional processes and employed local and highly skilled craftspeople.

Though this 1960s collection primarily centres on pieces of furniture, such as chairs and sideboards, other decorative elements of interior design carry just as much historical significance. The curtains in the collection were designed and crafted by Bute Fabrics, an organisation founded in 1947 by the 5th Marquess of Bute with the sole purpose of providing employment opportunities for service people returning home from the Second World War. In 1967, when the University opened, Bute Fabrics were commissioned to provide all the ‘furnishings’ for the Pathfoot Building.

The decisions made by the University in decorating the newly established institution were not purely aesthetic, but also motivated by a desire to support local craftspeople and manufacturers. While furniture and furnishings can often be overlooked in their quotidian nature, when we take the time to uncover the stories of these pieces and their significance, we learn of the people and the histories that they carry.

When viewing the furniture collection, one may wonder, is this art? Or: does this collection fall under the purview of the Art Collection? The answer to both questions is, surely, an assertive and emphatic “Yes!” Though these pieces may not hang on the gallery’s walls, they hold both aesthetic and social value: they are the creative products of artists, of skill and craft, and they express ideas. They are, unequivocally, artworks. And, therefore, the Art Collection cares for them.

This furniture collection holds the history of the University of Stirling within its upholstery. These pieces have witnessed over five decades of university life and have carried the burden of exam stress, the nerves of incoming first-year students, and the excitement of intellectual debates. Not only does this collection represent the aesthetic developments that characterised the 1960s, but it offers us a tangible connection to the generations of students and staff who have passed through the University of Stirling before us.

Written by Jess Riley, MA Art History and English, St Andrews.

The Art Collection is greatly indebted to Jess who has volunteered for us during most of this pandemic year, and amongst other tasks, has worked hard researching our furniture collection.

After the summer she is to embark on another chapter, studying for an MPhil in Heritage Studies at Cambridge University, and we wish her the very best of luck.