Our Digitisation Assistant Joel reflects on the beauty and value of rugby programmes.

I am now coming to the end of Phase 2 of University of Stirling Archives and Bill McLaren Foundation project to digitise materials from the archive of legendary rugby commentator, Bill McLaren. The first phase focused on letters, press cuttings, notes and materials relating to his work in rugby, his military service during World War 2, his career as a teacher and his personal life. Phase 2 has concentrated almost entirely on his extensive collection of rugby programmes.

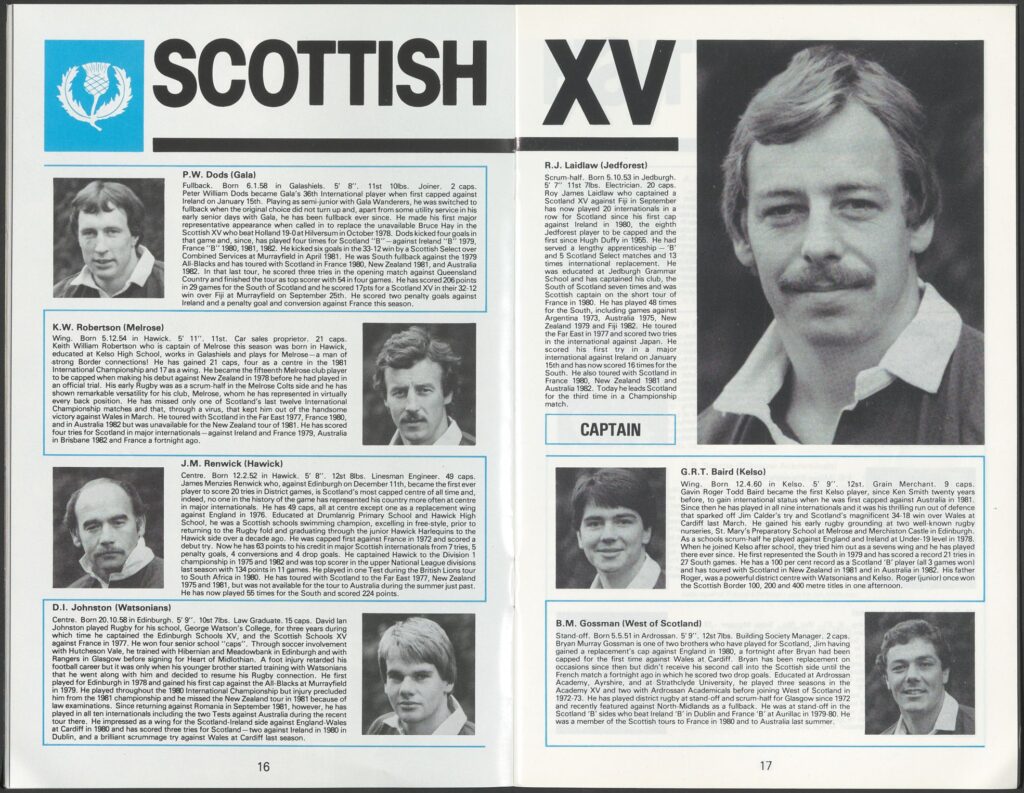

McLaren amassed programmes covering a comprehensive range of matches, primarily international games featuring the home nations. However, the collection of 698 programmes, dating from the 1920s to the early 2000s, that I have numbered and digitised during the project highlight the breadth of McLaren’s connection with the sport at all levels. There are programmes for youth matches, memorial or testimonial games, and regional games across the country. Some have enclosed notes and cuttings, and some have photographs, squad lists and other text cut out. I created a basic database to number the full collection and mark out those prioritised for digitisation. I noted publications with annotations, enclosed cuttings and notes, cut-out pages, publications of historic interest, and publications which include material written by McLaren. The project also worked with the Stirling County Rugby Club Memories Group, who used their expert knowledge to work through the collection and pick out significant games.

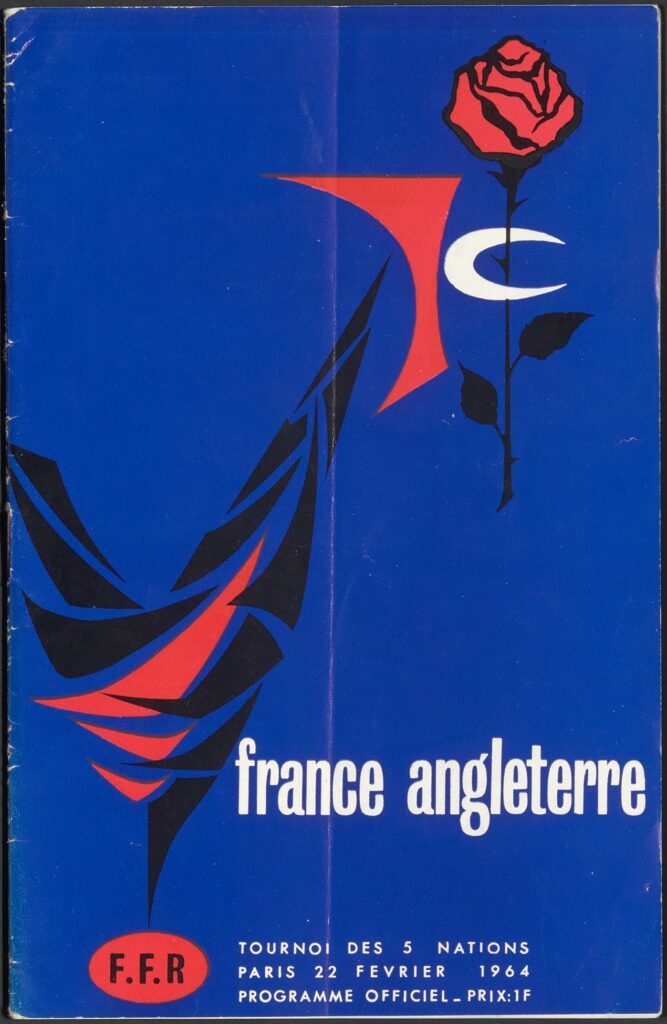

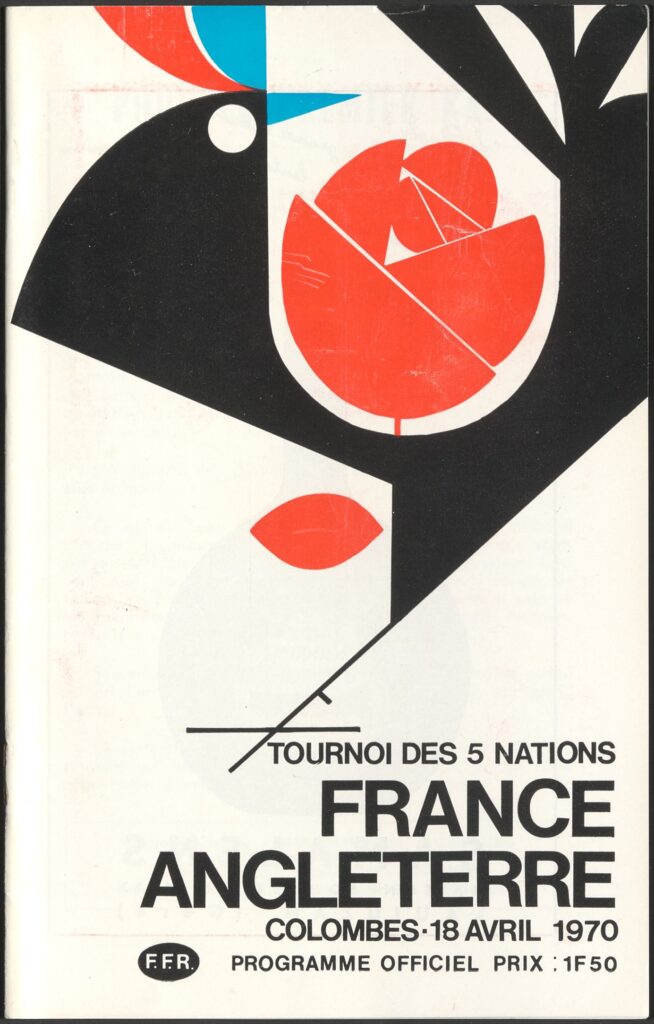

It has been impossible for me to sit and read the articles, editorials, and team-sheets that make up the majority of these programmes while keeping up the brisk pace of digitisation required. I have been more engaged while working by the visual significance of the collection. Much more so than the letters and notes I had been digitising previously, these programmes are visual documents: records of trends and changes in sports journalism, graphic design and advertising. Some of the covers – especially, it seems, his small collection of French programmes – are works of art in their own right, and I find the more recent trend for match photographs instead of these designs something of a loss, though some of the action photography on display is equally impressive!

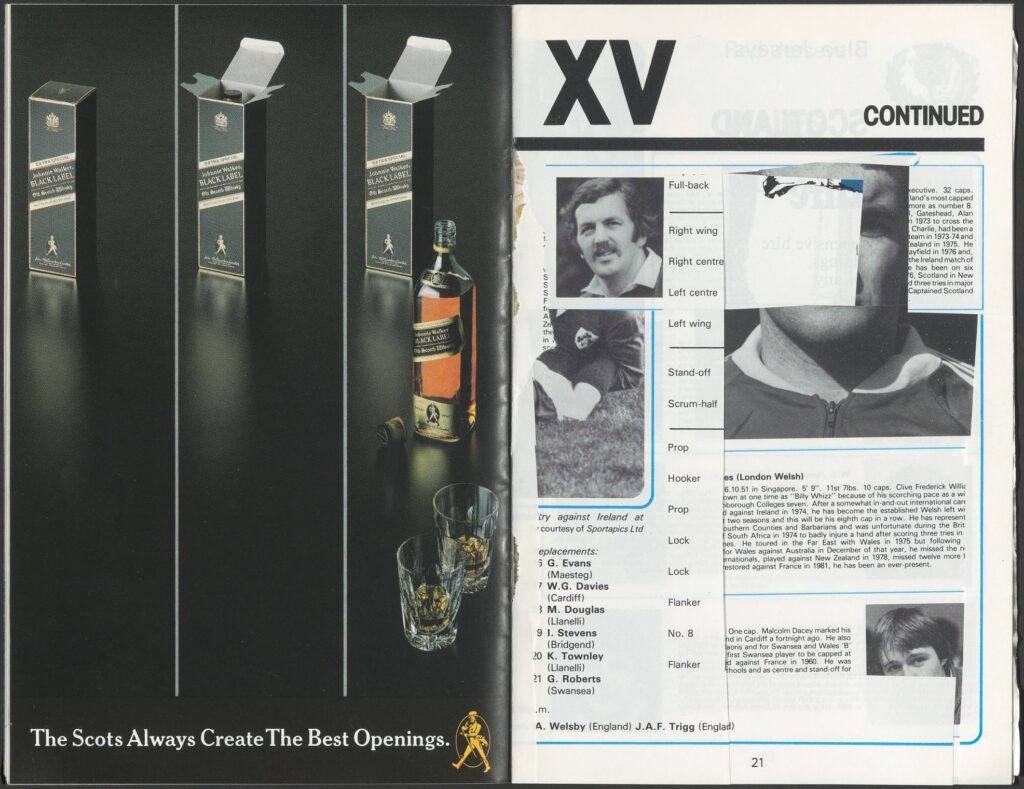

The other area of visual interest is the advertising inside programmes. There are advertisements present in all but the very earliest programmes Bill collected. Like the covers, many of these advertisements are engaging works of art and graphic design in themselves. They connect to rugby in creative ways and provide interesting evidence for the makeup of rugby audiences, or at least the way these audiences were imagined by advertisers. This advertising generally suggests what one might expect: that these programmes were aimed almost exclusively at men. Common products advertised are alcohol, aftershave, cigarettes and underwear, all aimed at men and often with dated sexist framing. I suspect it is true that it was primarily men who read, bought and collected these materials but how did women and children read and engage with them? Advertising provides a useful insight and it would be fascinating to conduct oral history research with rugby fans who attended matches and bought programmes across the twentieth century to see how the projected image of a rugby fan that we see in programmes matched up with the reality.

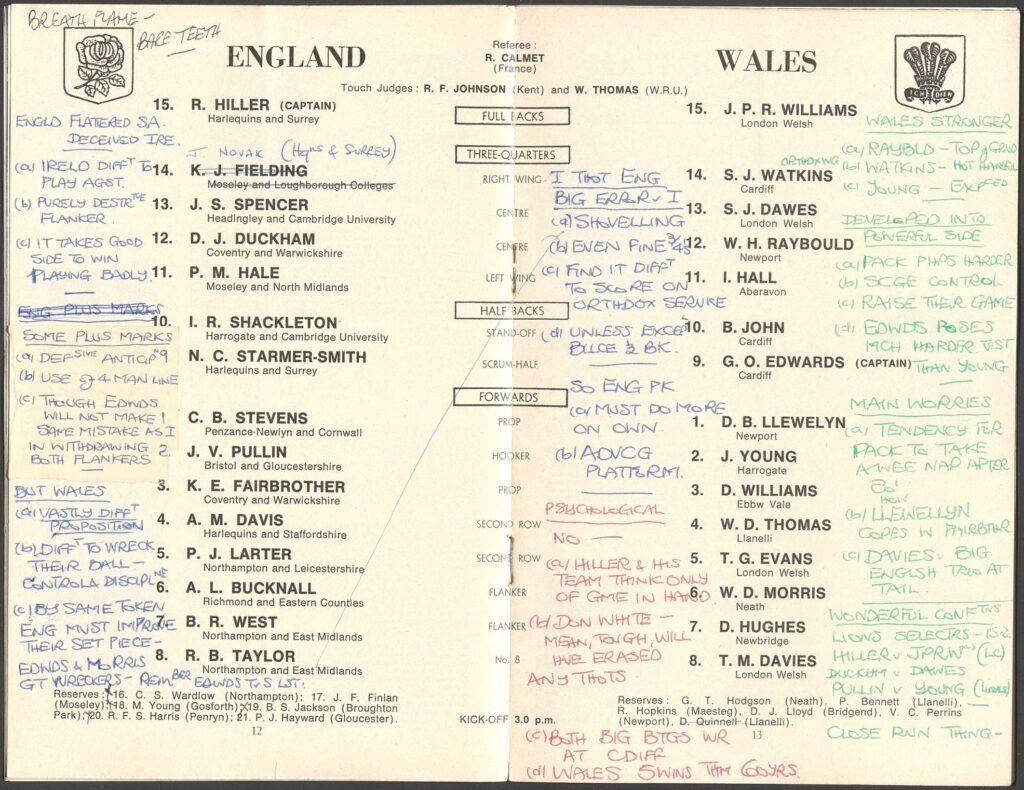

Many of the programmes also contain McLaren’s annotations, press cuttings and other documents. An England v Wales programme for 1970 (BMLD/2/5/243) contains colour-coded notes for commentary, with pre-prepared information on England’s previous matches and the ‘vastly different proposition’ that Wales will provide. These notes provide an interesting corollary to McLaren’s famous ‘big sheets’ and show the variety of ways he prepared for broadcasts. Programmes which include newspaper cuttings reporting on the finished game demonstrate McLaren’s fastidious attention to collecting and filing information on matches for later articles and commentary. More mysterious are the many programmes with sections cut out. I have not found any of the cuttings; we are left with the skeletons, the holes and missing information, except in the case of the programme for a 1983 Scotland v Wales game at Murrayfield (BMLD/2/5/294) which has a duplicate without cut-out sections to show us what was missing. He clearly used and re-used these documents in a variety of ways, providing us with an incredible insight into his preparations and process.

These programmes raise fascinating questions about the ways McLaren planned, organised and reflected on his analysis, commentary and writing, and how his work connects to broader cultural, social and political topics. After digitisation, the next step will be to ensure that these scans reach as broad an audience as possible of researchers, curators and rugby enthusiasts to begin to answer these questions (and of course raise new ones!). With all their notes and cuttings, the programmes were evidently living documents for McLaren, serving as more than a simple memento and continuing to inform his research and work after the final whistle blew. With their digitisation the programmes will be more accessible to a wider audience. Alongside Bill’s letters, notes and the other materials that make up his archive, they will ensure that the ‘voice of rugby’ will be heard and contemplated by generations to come.

Joel Casey, Digitisation Assistant